July 25, 2025

Australian industry not playing ball on R&D collaboration

In Australia, the Labor government has recently completed the largest review of the university sector in 15 years (the Universities Accord process), has established a new Australian Tertiary Education Commission and is also mid-way through a major review of Australia’s research and innovation system – the Strategic Examination of R&D, or SERD.

Both the Universities Accord and SERD reviews have noted the high quality of the research undertaken in Australian universities, and its centrality to the nation’s R&D system. But both have also repeated well-worn criticisms about Australia’s weakness in translating this research for commercialisation and innovation.

The Accord interim report cited Australia’s poor performance compared to OECD peers in the Global Innovation Index and found that better measures and evidence were needed to “indicate how useful our university research actually is to end-users”.

The SERD discussion paper, released earlier this year, took things a step further. It asserted that while Australian university research had grown significantly over the last 30 years, and was of high quality, “much of this research rarely addresses the needs of the main users of research and innovation in Australia – industry, government and the community”. The SERD also claimed that as more research has been funded by universities themselves (including from international student revenue), it was less strategic and less connected to industry needs. No evidence was provided in the discussion paper to back up these claims.

Taking international comparisons as their starting point, Australian policy and opinion pieces have tended to repeat these same old truisms and place the blame on research performing organisations. It is rarer in Australia to look at industry, to see how it is engaging with the leading edge of R&D. We decided to review the available data to see what it can tell us about the relationship between universities, industry and other end-users of research.

We compiled available data going back to 2000, including Australian Government data on research budgets and university income, as well as data on research publications. All of the data we have used is freely and openly available.

Far from evidence of a retreat from relevance, the story of the last 25 years is of increasing collaboration between Australian universities and end-users. This includes indicators of collaboration including co-authorship as well as direct funding. But once you start to dig into the data in more detail, there are some very interesting questions raised about Australia’s innovation system.

Since 2000, total research income to Australian universities from government, industry and international sources has risen significantly. Universities report income to government in four categories: competitive government grants (broadly curiosity-driven research); other funding from governments; income from industry, non-profits and international sources; and from Cooperative Research Centres (CRCs). Funding from all sources has risen faster than inflation with the exception of investment into the CRCs which has been flat.

Since 2017, it has been possible to break the publicly available data down into more detailed sub-categories. From this we can see that funding to universities from both Australian companies and international companies has continued to grow in recent years. Even through the COVID pandemic, companies continued to invest more in university research to assist them in meeting their own business goals.

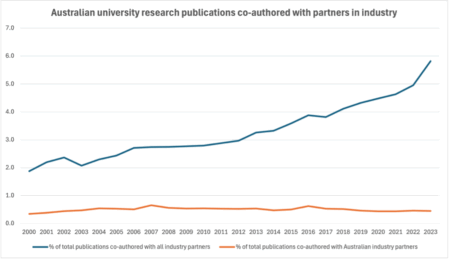

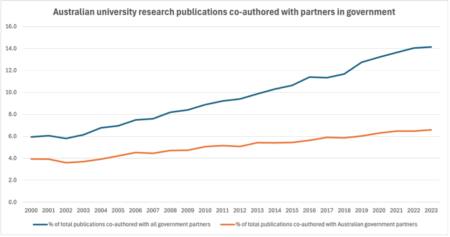

If we can see continued growth on the input side for collaborative research and industry engagement, is there evidence of a similar pattern on the output side? Looking at the data on research publications, we see a similar trend, with an increasing proportion of university outputs co-authored with partners in industry, government, and the non-profit and community sectors. Co-authorship on formal research publications is only one indicator of collaboration, but one with some interesting characteristics – it implies that collaborating authors are equal partners, both bringing intellectual capacity to the leading edge of research and innovation.

As the total number of research outputs from Australian universities has grown, so has the proportion of those that demonstrate collaboration with end-users. The proportion of publications co-authored with partners in government and the public sector more than doubled since 2000. The proportion co-authored with industry and the non-profit sector tripled in the same period.

These data are signals of both greater engagement and greater capacity for engagement. For Australian universities, this appears particularly strong with the public and not-for-profit sectors. The story of collaboration with industry is more complex. While overall the proportion of collaboration with industrial partners has risen strongly, that increase is almost entirely driven by collaboration with international companies, not Australian ones. While universities have demonstrated a clear capacity to lift their collaboration with commercial partners, it appears this does not translate well to Australian companies.

In contrast, when we look at the data on university collaboration with public and community sector partners, the rise in collaboration with international partners is mirrored by a rise in Australian collaborations. This is consistent with other analyses, for example the Leiden Ranking Open Edition. If there is a problem here, it seems to be specific to Australian industry.

To better understand what is going on with Australian industry, we examined other indicators of research and innovation. One potential indicator of the level of leading-edge research and innovation capacity is the level of publication from industry itself (or from government or the non-profit sector). Here a similar pattern emerges. If we look at levels of research publication from Australian industry, government and non-profit sectors, the contribution of government and non-profit entities to Australian research output is greater than that for comparator countries. But when we look at industry, the proportion is only 1% of the total, less than half of that in Japan, the UK, Netherlands, or Germany.

More than $4 billion of the Australian Government’s total annual R&D budget of $14 billion goes to R&D tax incentives to businesses. At 30% of the total government spend on R&D, this is the largest single line item in the annual R&D budget. When we look at the beneficiaries of that funding there are many organisations that don’t appear in research publication databases at all. Two top recipients, Atlassian and CSR, both appear and have credible research profiles in their areas. But many others receiving over $100 million in public funding generate little in the way of public research outputs and have no visible interactions with the research sector.

There are of course many pathways to innovation, that go beyond scholarly publishing. But collaboration for innovation is a two way street. The policy imperative for decades has been for universities to get better at engaging with the end-users of research. The evidence suggests that they have. What appears to be missing is capacity in Australian industry to engage and contribute.

In an ideal world, we would be able to say more in detail about what is going on, and why. We now make use of open source research data, but still face limitations in our capacity to link up research organisation information with the Australian business register, and from there onto more detailed sources of information including ABS business information (including the BLADE resource). We need to reinforce the call from the Universities Accord, to improve the evidence base – a relatively modest investment would allow a radical improvement in our capacity to link up and share useful data to inform policy and strategy.

The Accord recommended a new National Research Evaluation and Impact Framework, which would help to improve our understanding of Australia’s innovation capabilities (strengths and weakenesses) as well as the diverse pathways for research translation and impact.

We know that Australia’s economy is concentrated in a number of sectors, with limited capacity in manufacturing and technology areas that are associated with productive innovation systems in other countries. But we also have real strengths – Australia’s university researchers are world-beating in terms of their capacity and performance in collaboration, both within Australia in engagement with government and non-profit sectors, and also in tapping into the cutting-edge of knowledge and innovation globally.

Australia has lacked any comprehensive industrial or innovation policy for a decade since the National Innovation and Science Agenda in 2015. The last major intervention in the system was the former government’s University Research Commercialisation Action Plan in 2022, that started from a belief that the innovation problem lay with universities. The Accord has since recommended a new Solving Australia’s Challenges Fund to balance the focus on commercialisation and incentivise research translation across all sectors in areas of national priority.

The SERD, and the new Australian Tertiary Education Commission, should continue to focus on these issues, to ensure that the high-quality research in universities is supporting the broadest possible knowledge translation and innovation across all sectors, for the benefit of all Australians. To do better, and to be clear about where the problems actually lie, we will need better data and analysis. This will help us to set a strategy for the future based on our strengths, and not on outdated ideas of our weaknesses.

This article by IRU Executive Director Paul Harris and Dr Cameron Neylon was first published in Future Campus.